Experiences

Thanks to the amazing BIT guide and AA Route Planning Service, our route took us overland across France, Switzerland, Italy, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Turkey, Greece, Iran, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Tibet, and Afghanistan.

A trip that changed our lives

During our 9-month trip, we had many life changing experiences, many of which we recorded in our diaries, letters home and half frame 35mm colour transparencies.

We experienced the drab repression and corruption of Eastern European communism, the unexpected welcome and splendour of a secular Turkey, the brutality and repression of Iran's secret police, the Savak, the contradictions of Pakistan and India, the warmth and humour of the Nepalese, and the hospitality of the Afghan people.

Unfortunately, our plans began to unravel at the border between Nepal and Tibet where routes further east were closed and Gail's sickness forced our eventual return to the UK. But not before I had an experience on the shores of Lake Phewa (Pokhara) that would shape my life for the next 40+ years.

EASTERN EUROPE

YUGOSLAVIADon't smile, you are in Eastern Europe!

16th/17th March 1975:

Sunday night was spent in a picturesque and friendly village on the Adriatic coast, a few kilometres from Trieste.

Early on Monday morning we left Italy for Kozina, Yugoslavia (now Slovenia), some 15 km away.

Once over the border into Yugoslavia, we seemed to fall through an invisible portal into a time of bleak austerity and depression.

The people were unfriendly, the infrastructure crude and the country seemed in terminal decline.

As we drove the next 500km to Belgrade, the capital of Yugoslavia, our sense of foreboding increased. Something was not quite right, there were shifty looks between various ethnic groups and clear tensions between geographic regions.

Belgrade turned out to be a mass of modern concrete slums, overlaid with a sickening layer of bad smells. It was as if refuse had been left to rot on every spare patch of ground.

The air in the countryside was fresher, but farming remained primitive with strange looking bullocks pulling wooden carts and plough shares. Not a tractor was to be seen. Men sat in the bullock carts and the women walked as if in a trance alongside the animals. Roads became indescribably treacherous with long stretches of cobbles, made more dangerous by layers of mud and snow. Traffic was an endless stream of heavy lorries driven by seemingly suicidal drivers.

This oppressive atmosphere was made even worse by the endless wrecked and bloodied vehicles left by the roadside. The only sign of human compassion were the photos and flowers left at roadside memorials.

To add to our apprehension, we were stopped by a police officer in an incongruously bright blue VW Beetle. He was a brute of a man - grossly overweight, crew cut hair, scarred face and a menacing attitude.

"Passport!" he demanded. Well OK, we thought, it must be some sort of checkpoint. So, naively we handed over our blue British passports. After a cursory glance he quickly demanded 50 Dinar. "Why?", I asked. "Kar vasher, Kar vasher!", was his reply. I told him that I did not understand what he was saying, his curt response was "Hair kutter, hair kutter, 50 Dinar, give!".

This was to be our first introduction to official corruption and extortion on our trip. It was an unpleasant and disturbing experience that left a life long long impact on me.

Yugoslavs and travellers alike, had no choice other than to pay these 'fines'. Failure to comply with the demands of authority, no matter how unreasonable or unjust, could mean losing your freedom or worse. I was starting to realise how lucky I was to be British.

Welcome to communism - Eastern European style!

BULGARIASoviet propaganda & highway robbery.

19th/20th March 1975:

Early on Wednesday morning we crossed the border from Yugoslavia to Bulgaria. Once over the border people were surprisingly friendly and cheerful.

We were greeted by huge soviet style propaganda posters mounted on 5 metre high display boards. These typically portrayed a hard working citizen with a raised muscular arm, set against a background of a red hammer and sickle. They were like something out of George Orwell's "Nineteen Eighty-Four".

It was market day when we arrived in Sofia, the capital of Bulgaria. Every variety of local produce could be purchased from the stall owners. We purchased a small, heavy loaf of unleaven bread and some mouldy fruit - not the most appetising of food, but it was local and edible.

Soon we were searching for a safe place to spend the night. This was made fairly urgent by the threatening multilingual roadside signs. These stated that it was forbidden to sleep in our vehicle, either on, or near, the roads at night.

Luckily, we found a friendly farmer who directed us to a "closed" official campsite, where the entrance gate could be opened if the gate was lifted just a few centimetres.

Our Bulgarian transit visa was limited for a 48 hour period, so we left the "closed" campsite early the next day, and quickly headed towards the Turkish border.

On the road west we found ourselves stuck behind a broken down lorry. To pass the lorry we had to drive across a solid white line painted in the middle of the road. We were to soon discover that crossing a solid white line, even to pass a broken down vehicle, was a serious traffic violation in Bulgaria. But there was no other way to pass the lorry, and we needed to reach the border before our visas expired.

As soon as I had crossed the white line, a grinning policeman jumped out from in front of the lorry waving a small lollipop traffic signal.

We had been trapped in yet another Eastern European scam. The officer immediately demanded our passports, laughed, demanded money, and then finally walked away with our passports in his pocket.

If we stood our ground and argued, we would easily exceed our 48 hour visa and that would present us with far worse problems.

It was clearly hopeless, the officer had nothing to loose, yet we faced the loss of our passports, expired visas and even greater fines at the border. So I paid in the region of US $15 and we were on our way again.

We stopped at a lay-by about two hours later. Here, we met a very frightened German couple in their VW. They had been held up at pistol point by bandits near Agri, Turkey. In order to get away they had to throw money out of the window of their VW.

Our encounters with Soviet era police and stories of highway robbery were unnerving, but there could be no turning back now.

TURKEYIstanbul, the Pudding Shop and Sammy

:20th - 26th March 1975:

On reaching the Turkish border, we were met by rows of vehicles stripped bare by their owners on the orders of Turkish customs officials.

One customs official spotted a couple of Playboy magazines in the back of an Iranian owned BMW. These magazines were quickly confiscated. The owner of the BMW was then waved past more serious scrutiny as the official with the Playboy magazines had far more pressing distractions on his mind.

I made the mistake of asking a returning German, what it was like in Turkey. Sensing my apprehension, he simply replied: "They ate an Englishman last week"!

We were relieved to pass through this border without too much hassle or demands for yet more baksheesh. Our experiences with the Soviet era police in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, had shown us how vulnerable we really were.

Full of anticipation we drove off towards Istanbul, passing rolling hills interspersed with the domes and minarets of mosques. Young boys herded flocks of sheep and women wore colourful dresses over voluminous Turkish trousers.

The country now had a very exotic and vibrant feel; it was light years from the drab greyness of communist Eastern Europe. Capitalism was alive with Türkiye Is Bankasi welcoming us from every billboard.

As we drove along the Sea of Marmara we were rewarded with a beautiful sunset over a calm, yet misty sea. It had been a long day, so we chose to spend the night in a Mocamp on the outskirts of Istanbul.

Here we met an American couple driving a Land Rover back to the UK. They were totally freaked out, having spent 6 months in Nepal with hepatitis and then in custody in India, due to a ball bearing smuggling racket.

On Friday 21st March we drove into Istanbul to find the infamous Blue Mosque car park. The incredible traffic, chaotic streets, unexpected potholes and constant din of traffic, quickly disorientated us.

Then suddenly, right in front of us, jam packed with VW camper vans, Land Rovers and 2CVs, was the Blue Mosque car park. It was here that fit and cheerful east bound travellers would talk and trade with exhausted westbound travellers.

For the next 5 days we exchanged stories and vital supplies. We ate at the Pudding Shop and generally prepared ourselves for the big push east.

Sammy, the quasi hippie manager of the Pudding Shop, seemed to know just about every traveller and fixer in Istanbul.

One night Sammy introduced us to Tex, a spaced out dude from Texas who was avoiding the Vietnam draft by driving the Magic Bus from Amsterdam to Istanbul.

On our last night together we drank a lot of Raki and I felt homesick like never before.

TURKEY

The Blue Mosque and Baghdad doctor

(text coming shortly!)

***************************

ASIA

PAKISTANSaved by a Senior Civil Servant and Baluchi tribesmen

14th April 1975:

After crossing numerous desert roads and mountain passes, our convoy of three VWs arrived at a military check point just a few miles from Quetta.

The soldiers guarding the barrier told us that the last section of the pass had been closed at 18:00, due to increased bandit activity. The choice of being stuck at a military check point surrounded by bandits and pushing on to the relative security in Quetta, required little further debate.

Somehow I convinced the officer in charge that I had an urgent meeting with the Pakistani Ambassador in Quetta. Of course this was a total fabrication but it was a desperate situation. If I had met the Ambassador I would have confronted him over the false assurances he had given us in London. While obtaining our various travel documents at the Pakistani Embassy in London, the Ambassador had assured us there were no bandits in Pakistan and it was a very safe country to visit! He must have known a different Pakistan.

On arrival at Quetta we were exhausted and in need of serious rest and good food. But where could we stay that was safe? By chance I found a government Circuit House and was able to persuade the security guards to allow our VWs inside the gated compound.

I used the same story about needing to meet the Pakistani Ambassador, as I had used at the earlier mountain check point. Unfortunately the Circuit House manager was much harder to convince. No matter how thoroughly he examined the establishment's reservations, he could find no record of my proposed meeting with the Ambassador.

It soon looked as if the guards would be ejecting us, not only from the sanctuary of the house, but also from the security of the compound.

At the last moment help came from a Pakistani Under Secretary of State who had overheard our argument. With extraordinary good fortune and his compassion, all six of us were invited to share a meal with him that evening.

However, we could not stay inside the Circuit House, as there were no free rooms, but he would allow us to park our VWs in the security of the Circuit House compound. This was a perfect outcome for us.

With sand and dirt ingrained in our clothes and skin, we needed to clean ourselves up for the evening meal. Very kindly the same Under Secretary gave us use of his bathroom, although by now we were all pretty wary of such offers. It was amusing to observe how many vital items he needed to recover from his bathroom, whenever one of us was having a shower!

The evening meal was both delicious and sureal, as it was served with a formality that suggested we could indeed have been diplomatic staff. With the three travel stained VWs parked near to the external dining table, the meal felt as if Monty Python's Flying Circus had arrived in Quetta.

The next day, feeling a little red eyed and hung over, we visited the local fruit and vegetable market. This was an incredibly colourful place full of guavas, mangoes, pumpkins, aubergines, tangerines and papaya.

Amongst the piles of fruit and vegetable, sheep and goats roamed freely under the watchful eyes of charming peasant girls, each wearing dozens of small brass earrings.

Next day we tried to change money into Pakistani currency. Our US American Express Traveller's Cheques were changed without difficulty. Unfortunately Hans and Suzi tried to change Swiss Francs Travellers Cheques issued by the Bernese Central Bank. In Quetta, nobody had ever heard of the Bernese Central Bank and there was some doubt whether they had even heard of Switzerland.

The delays in changing money meant we were much later setting off for Sukkur than we had planned. This made us very nervous, as we knew we had to pass through notorious bandit country.

Help came in the shape of a disparate group of Baluchi tribesmen who, having been asked for help at a local Chai house, provided protection until we were out of danger. Their weaponry consisted of 12 bore shotguns, Lee- Enfield 0.303 rifles and the occasional Winchester rifle (all with the same serial numbers).

In 1975 there was not an AK47 to be seen.

INDIA

Cremations, drug smuggling, and raw mangos in Varanasi.

9th-12th May 1975:

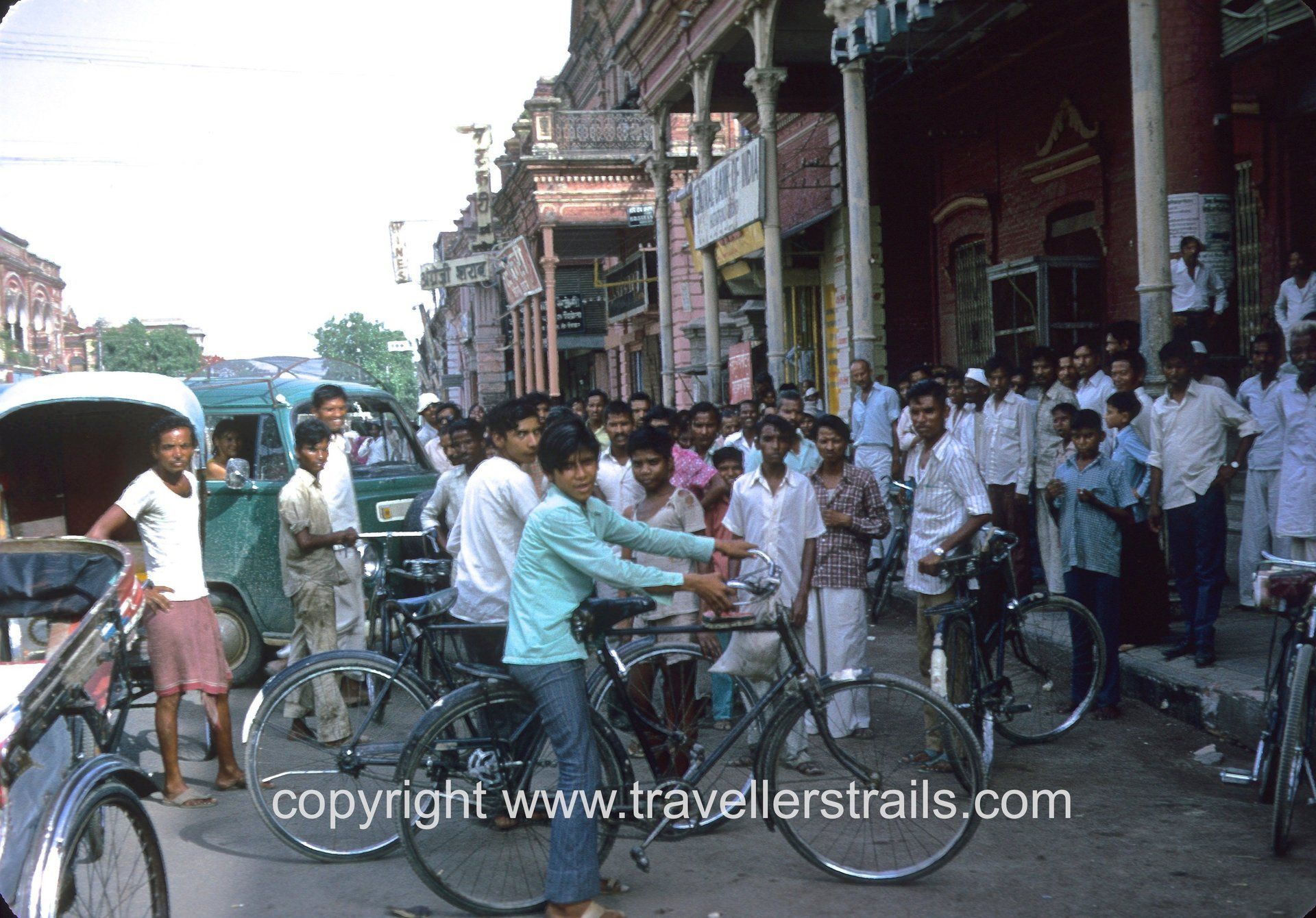

We spent the night in Mauganj, sleeping in our VWs parked in the grounds of a P.W.D. Bungalow. In the morning we were woken by a noisy commotion directly outside our VW. This turned out to be a crowd of at least 50 Indian youths and children. They were all jostling to see who or what was inside our two VW camper vans.

Unfortunately Gail was already weak and suffering from a splitting headache, following the long hot drive of the previous day. Her condition had deteriorated fast overnight and she now had terrible diarrhoea and stomach cramps. The relentless pressure of this noisy crowd quickly wore her down still further. Soon she was bursting into tears every five minutes or so, for little apparent reason.

Suzi was also starting to get rattled. The non stop questioning of: "Mister, Mister", "What is your name?", "What is your country?", "Where are you going?", "What is the time?", "What is your profession?", "What is your salary?", "Are you married?" was like some form of endless torture. Hans and I decided there was only one solution and that was to move on out towards Varanasi as quickly as possible.

We arrived in Varanasi (also known as Benares) situated on the banks of the Ganges, in a state of total exhaustion. Gail felt so bad she thought she was going to die, her weakness and growing depression not helped by the atmosphere of sickness, decay and death along the banks of the Ganges.

Varanasi is a city famous for its colourful silk fabrics, as well as being a major centre for Hindu pilgrimage. Hindus believe that death in the city will bring salvation, and as a result there are over 23,000 temples to various Hindu gods. These range from dilapidated stone outhouses containing a lone sacred cow, to the impressive Kashi Vishwanath Temple to the god Shiva.

The embankments of the Ganges in Varanasi are formed from stone slabs fashioned into large steps, some of which are used to cremate the dead. It is a strange and alien environment, particularly when you are not feeling too well or generally feeling vulnerable.

Bodies wrapped in cloth are burnt on wood fuelled fires on the 'burning ghats', while pilgrims and holy men cover themselves with the ashes of the recently cremated.

Even though sewage and partly burnt bodies can be seen in the river, the water is frequently drunk as a form of purification and total immersion in the water is regarded as an important cleansing act for pilgrims.

The next day we moved to a hotel so that Gail could recover in an air-conditioned room. Her recovery appeared to be painfully slow, and she was already showing signs of dehydration and salt deficiency. Even sipping water required unbelievable mental and physical effort. In the end, the hotel manager prepared a special meal of raw mango, which Gail eventually managed to swallow.

While she rested in the security of the air conditioned hotel room, I went in search of a chillum, as recommended by the BIT guide to India. In my naivety I had assumed that a chillum was some form of Indian drum, rather than a pipe for smoking hash.

I eventually came across a curious shop displaying various wooden musical instruments and carvings in the window. The owner appeared confused when I told him I was looking for a very special chillum, but suddenly he thought he knew what I was really looking to buy.

From then on he beamed with great pleasure as he showed me all manner of wooden ornaments and instruments with clever secret compartments. He assured me that they were the very best money could buy. He even offered to post them to me in the UK, ready loaded with the drugs of my choice!

This was not what I had been expecting at all, but as he had shared so many secrets with me, I could not leave without buying something. Eventually I made a low cost purchase, promising to return later for more significant purchases.

That night, Gail and I agreed to leave Varanasi without further delay and to aim for the cooler climate of Nepal.

We explained our plan to Hans and Suzi, but they wanted to spend more time in Varanasi, as well as visiting Patna and Bodh Gaya, before continuing onto Nepal. So we agreed to meet a few weeks later in Kathmandu.

Tragically, the four of us would never to be together again.

NEPAL

Magic Kingdom and a Tola of Temple.

13th-19th May 1975:

Gail's uncle Ian had been an officer with the Gurkhas during WW2, and had given us a copy of his notes for travelling between Raxaul to Kathmandu. These had been written with typical military precision (9 distinct paragraphs) and were dated 13/12/1946.

From Raxaul, the land became very fertile and surprisingly flat for the next 20 miles or so, until we reached the foothills of the Himalayas. Then, all of a sudden, there were no working animals to be seen. Instead there were masses of mango and banana trees and huge palms with pots tied to them, presumably to protect some kind of fruit.

Once we had gained some altitude into the foothills, we were surrounded by a luxuriant rain forest with enormous creeper vines extending high into the tree tops.

Paragraph 6 of Ian's notes advised us to "...make an early start from Sisagarhi to cover the distance of 15 miles to Trankote, which would take about 7 hours with a pony, dandy and coolies."

The notes went on to suggest that "...our coolie should be lightly laden with a suitcase and that we should carry our own tiffin. The baggage coolies would proceed at their own pace."

The descriptions of the countryside in these 30 year old notes, proved to be remarkably accurate, all the way up to the Chandrakirti Pass (7,700 ft above sea level). Even the original ropeway stations described in Ian's army notes, were still in use.

However it was now 1975 and we had the benefit of a reliable air cooled VW Kombi, and did not require a pony and dandy. This meant we were able to continue onto Kathmandu without the help of baggage coolies, a Chowkidar, a Bhisti or even a Sweeper!

After gaining more altitude, the rain forest vegetation became less verdant and lush. It was now increasingly red and brown in colour. Every inch of land as far as the eye could see had also been cultivated with terraces, right up to 8,000 ft and beyond.

Then quite unexpectedly, we could see the Kathmandu valley, a truly magical and inspiring place. It was as close to a forgotten land as we could ever have imagined.

On entering Kathmandu city near Durbar Square, we saw solid houses constructed from brick and stone. They had wooden eaves, shutters, balconies and doors, all beautifully carved in great detail.

With the countryside so appealing, we decided to spend the night in a small village just outside Kathmandu. This charming village consisted of staggeringly beautiful farmhouses and cottages, where people lived upstairs and their animals below.

The next morning we woke to a breathtaking spectacle of mist and cloud swirling around the Himalayas. We could not believe that such a beautiful country had remained so exquisite and untouched.

Later that morning while buying some local bread in Kathmandu, we met up with Wolfram and Ruth, the German couple we had left in Sukkur some 4 weeks earlier. It was a quirk of the Hippie Trail that people regularly bumped into each other as if it was the most natural thing in the world.

We asked if they had seen Hans and Suzi, but the answer was no. We were all worried for them, but we could do no more than leave a written message for them in the Kathmandu Tourist Office.

However, nothing could have prepared me for what was soon to follow.

INDIA

Stomach cramps, visas and a cunning plan.

26th -30th May 1975:

Our journey to Delhi via Lucknow and Bareilly was shared with Swiss Pete, the hippie we had picked up in Pokhara, and Dave and Ian from Oz, whom we had met at the Nepalese/Indian border. Their company made this otherwise rather dull journey to Delhi, so much more enjoyable. We shared jokes, exchanged stories and drank endless bottles of Coca-Cola and Fanta, as we navigated our way across northern India using an old Bartholomew School Atlas.

We arrived in Delhi on a Tuesday, which turned out to be a mistake, as apparently the Afghan Embassy was always closed on Tuesdays. So, resigned to at least another airless night in Delhi, we searched for somewhere to stay. Eventually at 18:00, we found a guesthouse that claimed to have free space. It was not somewhere we would normally have chosen, it was more like a detention centre than a guest-house, but by now we had little energy left. Gail was also complaining of back and stomach pains, so we all tried hard to make the best of a bad situation. Travelling overland had given us new insights into the meaning of frustration and fatigue.

Once committed to the guesthouse, we found it was already filled to capacity with hippies, travellers, 'freaks' and bed bugs. What made it worse, was that the majority of the human guests were either stoned, half starved, half mad or in some cases, all of these. The most frightening were the European 'freaks' who tried to rummage amongst our possessions if given the slightest opportunity. Most of the other guests were waiting for money to arrive, but from where was something of a mystery.

I tried to see the upside of this experience, but soon realised it was not helping Gail, so in desperation I pleaded with the manager to find us a more 'private room'. He found us a converted store room in the corner of the ground floor, but the Indian string beds were longer than the room, and we had to sleep with our feet sticking out into the corridor.

Gail's condition began to deteriorate fast, making me feel totally helpless, as nothing I did seemed to help. I had never seen her like this before, as up until a few weeks earlier she had always been pragmatic and just got on with the challenges of life, but that had now changed. The only solution I could think of was to get her out of this alien environment, and to do so as quickly as possible.

After an emotional night we made ourselves a European style breakfast in a cool cellar we discovered close to the guesthouse. This breakfast gave us all an immediate boost, and we were soon on our way to the Afghan Embassy to apply for our visas. What could possibly go wrong?

Well, it turns out that the Afghan Embassy needed 24 hours to prepare visas, which meant we had yet another hot and airless night to spend in Delhi. Gail was now becoming quite disruptive, so I persuaded her to return to the chilled cellar where we had eaten breakfast, and to rest there for the rest of the day. I then rejoined Dave and Ian for our next challenge of changing money into Indian rupees.

After more than 4 hours, none of us could find a bank willing to help, even the State Bank of India declined to change our American Express Traveller’s Cheques or US $ cash. Once again exhausted, we trudged back to what we were now calling our Hippie P.O.W. Camp. During the night Dave, Ian and I took 2-hour shifts to ensure the 'freaks' left our possessions alone. This meant that those of us not on watch were able to sleep with a degree of security.

When morning arrived, we immediately drove to the Embassy to pick up our new visas. Shortly after this momentous moment, either in elation or desperation, I found an affordable hotel with a large air-conditioned room and comfortable bedding. The difference between the hotel and guesthouse was like heaven and hell. The hotel was clean, quiet and there were no 'freaks' trying to rob us. In this calm environment we made plans to leave early the next day. We then made our farewells to Pete, Dave and Ian, as they wanted to spend more time in Delhi, promising to meet up again in Afghanistan.

Next morning, after the first good night’s sleep in nearly a week, we set off for the border at Wagah.Unbelievably, the Indian customs only glanced at our VW, although our travel documents were repeatedly checked before we were cleared to leave for Pakistan. Luckily the Pakistani customs were less bureaucratic and let us through quickly. Soon we were well on our way to Lahore, but Gail was once again in considerable pain.

Then all of a sudden, out of total desperation, I thought of a cunning plan - it was probably unethical, but it was the best I could do.

KHYBER PASS & KABUL GORGE

A 5* plan, vanilla ice-cream

and a close encounter

30th May - 1st June 1975:

I needed a plan to find a doctor and I needed it quick.

The doctor would need to be credible and able to explain in good English what was causing Gail so much pain. The fastest and most likely way I could think of, was to go to a major international 5* hotel and seek help from the hotel doctor. If Gail could eat some hotel food first, that might ensure some ownership of her discomfort by the hotel.

Finding a high rise 5* hotel in Lahore was going to be fairly easy, the challenge was going to be entering the hotel as if nothing was wrong.

About a month earlier we had spent some time by the pool at the Intercontinental Hotel Karachi, and were therefore pretty familiar with the chain’s general layout and its high standards. So having found Lahore’s Intercontinental Hotel, we parked our VW in the hotel car park and entered the lobby looking confident and self-assured.

Once inside, we asked directions to a restaurant where we could have a light snack and some cool drinks.

The staff were as helpful as we had expected, and soon Gail was eating a hotel prepared ice cream and drinking yet another Coca-Cola. After about 45 minutes, Gail started to complain of stomach pains, so I asked the hotel manager if he could call the hotel doctor. He did this without hesitation and although he may well have done so without our little bit of theatre, it was a risk I was not prepared to take.

The doctor arrived quickly and after paying his fee, Gail was examined on the hotel manager’s desk. After much poking and prodding he drew a very basic picture of her anatomy with an arrow pointing vaguely in the direction of her stomach. He also gave her some medicine for indigestion and suggested I should take her to Lahore’s United Christian Hospital for observation and a complete rest.

After some time we eventually found the hospital, but its reception area was full of really sick and injured people. After a couple of hours waiting, Gail concluded that the smells and noise in the hospital were probably worse than her sickness. So we agreed another plan, that was to now head for Peshawar the next day, where we thought the medical facilities would be better. We also thought there were likely to be more US or UK trained doctors available.

In the meanwhile, we found another reasonably priced hotel in which to catch up on our much-needed rest. The next day we set off for Peshawar early in the morning, arriving at Rawalpindi’s Intercontinental Hotel for a light lunch of Spaghetti Bolognese. Here we stayed for the hottest 4 hours of the day, before completing our onward journey to Peshawar.

We arrived in Peshawar in the early evening and found it far more developed than the towns we had seen in southern Pakistan. The women also seemed less repressed and the men more alert and friendly.

I quickly found a suitable hotel where we could stay, as well as finding a Chowkidar to look after the security of our VW.

Although still unable to eat, Gail was becoming less tearful and more like her old self. Later that evening after settling into our room, I ordered a chicken curry via room service. This meal arrived while I was having a shower, but when I had finished, all the food had disappeared – somehow Gail had suddenly recovered her appetite.

After probably the best and most restful night’s sleep for months, we were on the road to the Khyber Pass at 07:00 the next morning, our intention being to reach Kabul before darkness.

As we approached the area of the Khyber Pass Gate, the countryside became very rugged and mountainous. All the men in the region wore tribal turbans and carried an assortment of rifles and fully loaded ammunition belts. The whole area looked like something from a Hollywood film set, but an abundance of government signs warned travellers of the very real dangers of this area.

It was forbidden to enter the Khyber Pass at night and travellers were warned not to deviate from the guarded areas during daylight. These signs were accompanied by other notices that made it clear that because the Khyber Pass was in a tribal area, the Pakistani Government would accept no responsibility for the safety of any traveller.

The Pass itself was an impressive place, consisting of some 25 miles of fairly mild inclines and bends with armed guards strategically placed every few hundred meters. All the villages were fortified and high up in the rocks you could clearly see beautifully carved badges of the British regiments who fought in the Anglo Afghan wars of the 19th century.

At one stage we took a wrong turning and ended up in a cul de sac in a fortified tribal village. Just as I was trying to reverse out, we were confronted with a fully armed man offering us a huge slab of local hash. He was very insistent that we take the hash, but we declined, smiled graciously, and got out as quickly as possible. We were later to learn that this was part of a local ‘scam’ and if we had ‘bought’ the hash, he would have informed the next customs post. We would then have been arrested and fined, while our grinning friend would once again pick up a reward and his slab of hash!

The Khyber Pass border appeared far more civilized than the border we had crossed when entering Pakistan from Iran, although the exit checks were again minimal. Once we had reached the Afghan border, we had a pile of forms to complete and then, after another mile into Afghanistan, our vehicle was thoroughly searched at a surprise check point.

We were now set to pass through the Kabul Gorge where the local people had strong Arab like faces and appeared friendly and dressed with real style. The scenery was also very beautiful and we passed high rock faces with impressive waterfalls of white foaming water, beautiful green lakes and a clear blue sky.

When we eventually approached Kabul we were surprised at how civilized everywhere seemed to be, the suburbs were reasonably clean, buildings were solid and the police even wore smartly pressed uniforms.

Best of all, Afghan food was delicious, and eating out in Chicken Street was like one long party.

AFGHANISTAN

A birthday party in Kabul and a ghost hotel en route to Herat!

5th - 8th June 1975:

We decided to hold my 28th birthday in a fairly basic traveller's hotel in Kabul. Gail had commissioned a birthday cake made from coconut sponge, strawberry jam, white icing and topped off with birthday greetings piped in chocolate.

My birthday party suddenly doubled in size when we discovered Dave and Ian (last seen in Delhi) getting off a beaten up bus from Pakistan. They were accompanied by a new Irish friend called Murphy. All three were invited to my birthday party, together with a couple of young Afghani lads from the local Buzkashi stable.

My birthday party was one of the most enjoyable I could remember. We ate herbal based brownies, slices of my birthday cake with 'HAPP Y BIRTHDAY MIKE' (sic) piped on the icing and consumed vast quantities of fresh strawberries. All this food was washed down with copious quantities of Irish jokes, local tea and out of tune singing.

Early next morning, although tired and once again red eyed, we set off for Kandahar on a fast road with little or no traffic. We passed through beautiful green fir trees on the edge of Kabul and then staggeringly impressive rugged mountains as we approached Kandahar.

We passed hundreds of nomadic Kochi people walking around their encampments, which were set back from the main highway. Women wore spectacularly colourful Kochi dresses and their highly polished metal jewellery sparkled in the desert sun.

At around 16:00 we arrived in Kandahar, but due to the heat and abundance of flies, decided to treat ourselves to a stay in the Peace Hotel. This had the additional benefit of a reasonably secure garden in which we could park our VW.

By now we were really hungry and Gail seemed to be recovering well from her earlier illness, so we set off to find a local restaurant. Here we ate Ashak, ravioli stuffed with leek and a meat sauce, covered in yogurt and surrounded with chalaw meat balls and rice. Delicious!

Overall, Kandahar was disappointing after the excitement of Kabul and offered little of historic or cultural interest. After eating such an enjoyable meal we decided on an early night to prepare ourselves for the next leg of our journey across Afghanistan.

At daylight we quickly changed money so that we could purchase 140 litres of cheap low octane Russian petrol and pay the road tolls or 'taxes' that lay ahead. Between Kandahar and Herat enterprising individuals were known to set up arbitrary barriers so they could charge an 'exit tax'.

The road outside Kandahar took us past impressive mountain scenery where the boys and men wore embroidered smocks with mirror work, very much in the style of Kochi dresses. The older men looked dignified and elegant in their huge white turbans.

In the desert, close to the foothills of the mountains, we came across huge swathes of brilliant dry purple flowers that 'sang' in the hot desert wind.

Occasionally, we had to navigate our VW around camel trains that had wandered across the road. The camel train leaders could be seen some way off, keeping their distance from the road while tracking the progress of their camels.

At around 15:00 we thought we could see a blurred image of a modern hotel complex on the horizon. There was no mention of this in any of our literature, so we assumed it was a mirage of a distant Iranian hotel.

However after a few more kilometres, the image became sharper. It was no mirage, it was a hotel or something very similar.

When we approached the entrance road to the complex we noticed there was no sign of life. No vehicles, staff or guests could be seen, although by looking through the huge plate glass windows we could see a fully furnished reception area and dining room .

On entering the reception area I had expected some relief from the intense desert heat, but the AC was not working even though there were AC outlets in the ceilings of every room. We found our way to the kitchen and found it to be fully equipped with unused stainless steel appliances.

The mystery deepened until the silence was broken by the sound of chickens coming from the rear of the building. Here we found a lone Chowkidar preparing some chai on a small camp fire. Through sign language, mime and theatre, we discovered that the hotel had been built by the Soviet Union. The deal had been for the Soviets to build a tourist hotel in exchange for unspecified local mineral rights.

Unfortunately the Soviets had rather inconveniently overlooked the need for water and electricity. So the complex had never been occupied by staff or guests.

The Chowkidar apologised for the oversight of the Soviets and offered to prepare two omelettes for us on his camp fire.

These omelettes were world class and worthy of any 5* hotel - even one without electricity and water.

AFGHANISTAN / IRAN

Iranian customs, dried potato powder

and a humour bypass.

(text coming shorty)

***********************************

IRANReunited with Hans in Takht Jamshid, Tehran

19th June 1975:

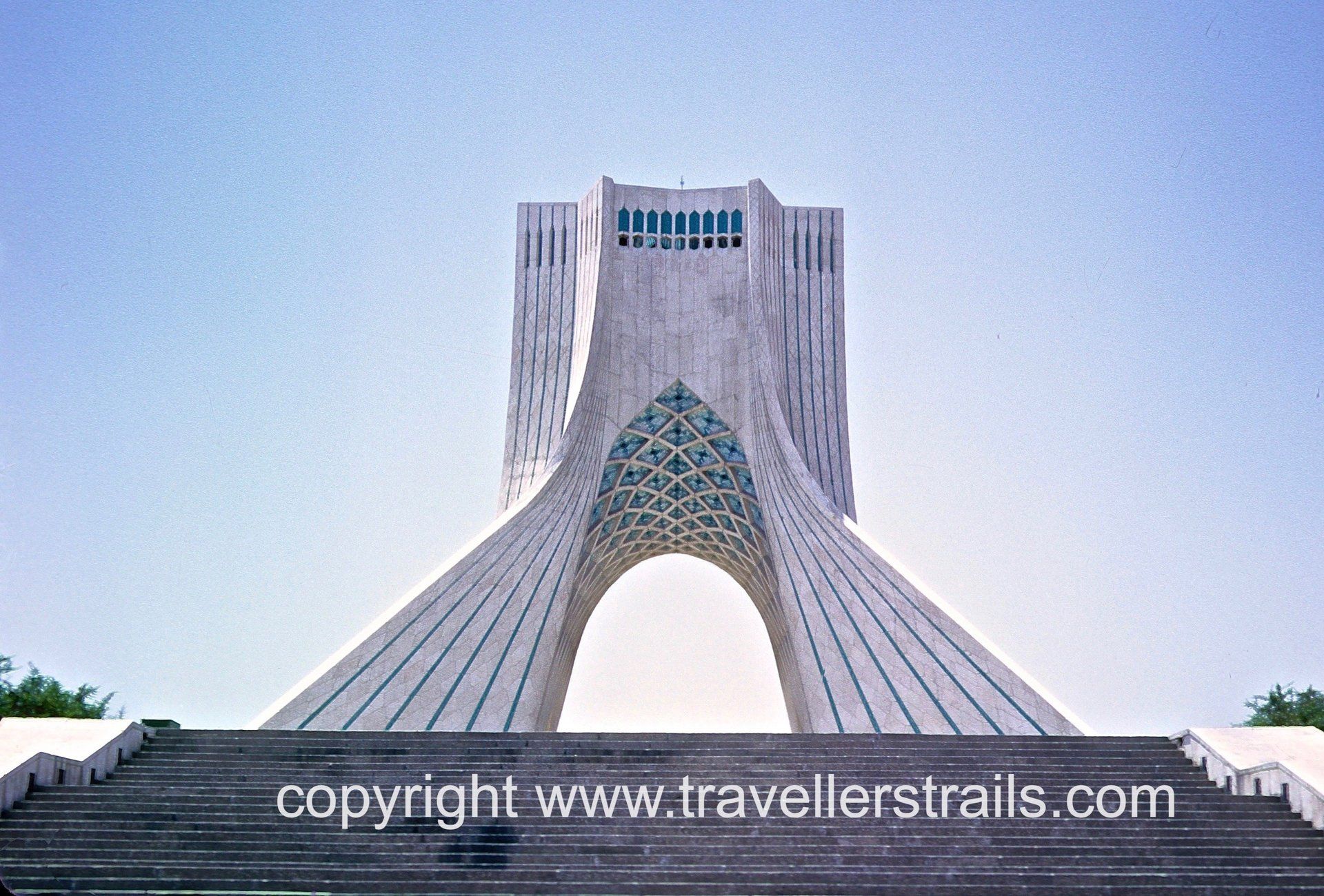

This was to be our last day in Tehran, so we decided to visit the Shahyad Tower, an elegant example of contemporary architecture containing an audio-visual portrayal of the history of Iran.

The first exhibition room displayed a constantly changing backcloth of the earth, mountains, fiery sunsets, clouds and sea - all projected onto large strategically placed boulders. Idealised images of Persepolis and ancient Persian culture were also on show.

The 2nd room was covered in pictures of Medieval mosques, minarets and examples of 16th century mosaics and tiles.

The 3rd room consisted of an endless loop projection of Iranian designs and initiatives. There were colourful pictures of kings, birds and sumptuous banquets.

The 4th and last floor of the audio-visual extravaganza, covered the modern age of Iran, with pictures of the Shah, his crown, oil fields and folk dancing.

These displays although over romanticised, had been arranged with a creativity that made a welcome change from the 'get rich quick' culture of everyday Tehran.

After a quick look around the fourth room, we took a lift to the top of the tower and were rewarded with a bird's eye view of the mountains north of Tehran. Unfortunately a yellowy black layer of smog could also be seen hovering menacingly over the city.

On our way back to John and Sue's house, we tried to change American Express Traveller's Cheques for US dollars, but the manager of the Amex office was nowhere to be seen. So off we went to find the Ferdowsi money changers, where we were able to convert our remaining cash into Iranian Rials and Turkish Lira.

On our return to our VW, I was approached by a young man asking "Anything for sale Mister?" Well, this was too good to be true, and I was able to sell a broken travelling clock, a surplus 20L Nato fuel can, and a superfluous torch for £10. We were then offered 4,000 Rials (equivalent to £28 in 1975) for an Indian rush chair that had only cost us 75p a few weeks earlier. But we could not bear to part with it, so it stayed in the back of the VW until we returned home to the UK.

We carried on back to John and Sue's home via Takht Jamshid, when there to our amazement, parked in the road, was Hans and Suzi's blue VW Camper. We had lost contact with them over a month earlier, when they failed to show at our pre-arranged meeting point in Kathmandu.

I desperately searched the local shops and eventually found Hans alone in the Government Tourist Shop, negotiating the purchase of an engraved brass tray. Neither of us could believe that we had at last found each other - but where was Suzi?

Apparently she had been taken ill in India, and although Hans was a qualified medical doctor, Suzi had spent 10 days in Amritsar Hospital. Here her sickness was made worse by the infectious vomit and faeces left on the walls and floor of the ward and the use of unsterilised syringes.

Eventually Suzi was medically evacuated by Swiss Air back to Switzerland where she was found to be suffering from Meningitis. Having made sure Suzi was safely on her flight home, Hans was left exhausted, robbed and stuck at Indian customs.

How Hans made it safely to Tehran with most of their possessions, was a mystery to us. Many of the high value items they carried were in Suzi's name and with her back in Switzerland, Hans would have had endless problems explaining her absence at border crossings. But, here he was in Tehran andJohn and Sue made him very welcome. After a shower, some good food and stimulating conversation, he regained his optimistic personality.

That evening Gail and I had been invited to join John and Sue at a British Embassy pool party. But having found Hans, we decided reluctantly to miss the Embassy party. Instead we spent the whole night talking with Hans about Suzi and sharing our various experiences since we were together in India.

The next day was a Friday (an equivalent of a Sunday in the UK) and Hans faced the almost impossible task of starting work at a new hospital in Switzerland, the following Monday.

This meant he would have to drive more than 4,800 km in less than 72 hours. At best Hans would have to survive on less than 5 hours sleep each night.

IRAN

Don't mess with the secret police of Imperial Iran!

20th June 1975:

We set off at 11:30 from John and Sue's house, having consumed a good breakfast and promising to meet them back in the UK at Christmas time.

It was General Election Day in Iran, so Tehran traffic was even more chaotic than usual. Somehow we navigated our way west across town to reach Qazvin in time to buy yoghurt, fruit, vegetables and eggs. We then made a huge bowl of fresh muesli to help sustain Hans on his epic journey back to Switzerland.

On the road out of Qazvin we noticed a badly damaged car in a ditch, just off the main road. There were two soldiers examining this car and a passenger could clearly be seen trapped inside. We stopped to help, as both our vehicles carried first aid equipment.

Strangely, the soldiers were talking to the man in the car but were not helping him. When they saw us approaching they tried to wave us away and then, because we continued walking towards the car, they simply walked away.

It was now around 14:30 and the inside of the car was like an oven. The man inside appeared to be very confused and in need of urgent attention. As Hans was a medical doctor our first thoughts were to help the injured passenger, but we could not understand the behaviour of the soldiers. Why had they not helped him?

As we tried to remove the injured passenger from the car, he tried to push us away. It was not long before a crowd of young men gathered around the damaged car and the atmosphere became increasingly hostile. Suddenly the injured man pleaded with us to leave him, saying "Savak, go", "Savak take brother, go, go!".

We were to learn that his brother had been driving the car when it had been forced off the road by the Savak (Iran's brutal Secret Police), more than 6 hours earlier. They had dragged his brother away and it was clear that not only was he in deep trouble, but so would everyone of his family and probably anyone known to associate with him.

The injured passenger had remained in the car to both protect his brother's car and to avoid further physical contact with Savak supporters. But having been in the car for more than 6 hours he was now very weak and extremely dehydrated.

We could only assume that nobody would help him because they were also afraid of the repercussions from the Savak. As naive Europeans we just pulled him out of the car, placed him in the shade of a nearby tree as Hans tented to his medical needs. Hans concluded that the injured man's most serious problem was shock and dehydration.

After ensuring he was rehydrated, and in a more stable condition, we were ready to move on. However, by now the crowd had become far more threatening and were demanding water, food, money and anything that took their fancy.

The ringleaders were clearly ready to pick a fight and it came to a head, when a young man on a motor bike tried to grope Gail.

When I intervened, the motor cyclist threatened to smash an empty coke bottle over my head. I then made the mistake of laughing at him in front of the crowd, at which point he pulled a knife.

We were now in deep trouble and it was his turn to laugh. It was by sheer luck that I had left an antique inlaid percussion cap pistol (a birthday present given to me in Kabul) on the driver's side parcel shelf of our VW.

I was able to grab this almost theatrical gun, and after pointing it at the trouble maker, the crowd moved back and we gained sufficient space and time to make a very hurried get away.

I am not sure how we would have felt if we had driven on past the crashed car, but later that day we concluded it was sometimes better not to get involved. This was some of the good advice we had been given by a British long distance lorry driver some 3 months earlier.

From Qazvin onwards the countryside became unrecognisable. It had changed from the barren rocky landscapes of early spring, to a green and fertile land, a bright patchwork of vivid green and gold.

That evening after preparing our VW for the next stage of our journey home, I reversed straight into Han's VW. I could not explain it then and I cannot explain it now - for some reason I just forgot his vehicle was behind us.

Hans was typically calm and just accepted the accident as one of those things. He then set about preparing a delicious Swiss Fondue to celebrate our last supper together.

The sheer lunacy of eating a fondue in the desert after a day of such high drama, was perhaps, what kept us going.

After all, we were travellers, not tourists.

.